“In It I Found My Deliverance: A Close Reading of an Irish Nationalist Broadside”

Chris. A. Gallagher, “God Save Ireland,” Minneapolis: Emerald Publishing Company, 1895. Osher Map Library Collection, University of Southern Maine.

“God Save Ireland,” a chromolithographic broadside that was acquired by the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education at the University of Southern Maine in the summer of 2023. This broadside was part of an auction lot, and it was described as a piece of pro-immigration propaganda designed to get Irish people to move to America, though, as I will demonstrate, that was certainly not the case.

“God Save Ireland” was produced by the Emerald Publishing Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and is a beautifully preserved piece of late-19th century Irish Nationalist propaganda. With an 1895 copyright attributed to Chris. A. Gallagher, the broadside, which may have been the only item that Emerald Publishing Company produced, appears to have been designed to raise money and awareness for the Irish Republican Nationalist cause in Ireland amongst Irish Americans. Indeed, the broadside’s very title can be read as the first part of the sentiment “God Save Ireland from the English,” the secondary clause being implied.

As far as I can tell, the Emerald Publishing Company existed solely to produce this broadside. There is no record of them anywhere else, that I have been able to trace, although it is possible that those exist in Minneapolis in undigitized local records. However, the publisher appears to be Christopher A. Gallagher, a Catholic lawyer from Manchester, New Hampshire, who founded the Emerald Toilet Company (a parfumerie) in 1897 after the loss of his hearing forced him to give up practicing law.

His parents, Richard and Cecelia Gallagher, were both ethnically Irish. He’s quoted in a handful of local newspapers in Massachusetts and New Hampshire in the 1880s railing against anti-Catholic and anti-Irish politics. Christopher was a strong advocate of organized labor, which he continued after his move to Minnesota in 1886, and he was also a member of the Land League. He died in 1921, and was buried back in Manchester in what appears to be a family plot.

The broadside’s imagery is divided into two sections; on the left, there are depicted scenes of English colonial atrocities perpetrated against the Irish in Ireland. This portion of the broadside bears the legend “English Argument on Irish Soil.” We will explore each of these images in descending order. At the top, there are images of barefoot Irish peasants - primarily women and children - being evicted from thatched cottages by armed soldiers in traditional British red coats while well-dressed men in frock coats and fashionable hats look on. This is an obvious reference to the rackrenting and eviction schemes that became endemic throughout Ireland in the 19th century, through which English and Anglo-Irish landlords would increase the rent on their Irish (and predominantly Catholic) tenants until they could no longer afford to pay, and could therefore legally be evicted. Evictions were popular amongst landlords in the post-enclosure period as landowners found it to be more lucrative to use formerly occupied land for grazing or cash crops.

Below the eviction scene, there are two images side by side. In the image on the left, an English judge is shown holding a rope from behind his bench; the rope is attached to the neck of a bound man standing in the docket, dressed in a brown coat. This seems to indicate that the judge has already condemned the man to death. To the right, there is an image of an English constable holding a man by the throat and brandishing a billy club; and if you look closely, you can see that the word “Coercion” is written on the billy club, which is likely a reference to the Coercion Act. The man appears to be falling to his knees; one hand grips the constable’s hand at his throat while the other hangs helplessly at his side. Although the man does not appear to be fighting back, the constable is shown ready to bring the coercive billy club down on the man’s head. Taken together, these images are designed to demonstrate that there was no legal justice for the Irish under English colonial rule; the Irish were at the mercy of violent constables and partial judges. The brutality of these images is intended to drive home to the viewer that the Irish lacked institutional recourse for their unjust and inhumane treatment at the hands of the English.

The image below these two is that of a sailing vessel flying a red flag with a Union Jack in the upper left corner: the Red Ensign of 1801 which was flown by the British Royal Navy until 1864. The landmass behind the vessel is labeled “Van-Diemen’s Land.” As Van Diemen’s Land, which was renamed Tasmania by 1856, it seems likely that this scene is intended to reference the transportation of criminalized Irish dissenters to the penal colony of New South Wales in the Famine and post-Famine eras. In concert with the indictment of the biased judicial system in colonial Ireland, this serves to unite the images on the left of the broadside into a compelling narrative: faced with rackrenting, eviction, and legal injustice, Irish individuals - primarily men - who attempted to defy their English colonizers would be criminalized and punished with transportation. while women and children would be left at the mercy of the English – likely to starve.

The final images on the left of the broadside show a man standing in what might be a witness box, leaning over the side with a smug look on his face. In one hand, he grasps a full moneybag, marked with an English pound; the box beneath his leaning arm is crudely marked “INFORMER,” indicating that he has been bribed by the English. (Slide 13) To the right, a scene similar to the eviction shown above is displayed, labeled “1847 Famine.” This, obviously, refers to the infamous potato blight that devastated the Irish peasantry from roughly 1845 - 1852, known of course in Irish as An Gorta Mór: the Great Hunger. Ireland continued to produce abundant crops throughout the years of 1845 - 1852, however these crops were intended for consumption by the Anglo-Irish ascendancy class, or for exportation to England. 1847 was widely understood to be the worst year of the Great Hunger as record numbers of poor, rural Irish died of starvation and disease. Taken together, the images depicted above the legend “English Argument on Irish Soil” are intended to convey a culture of institutional cruelty, exploitation, and injustice perpetrated upon the Irish by the English colonists.

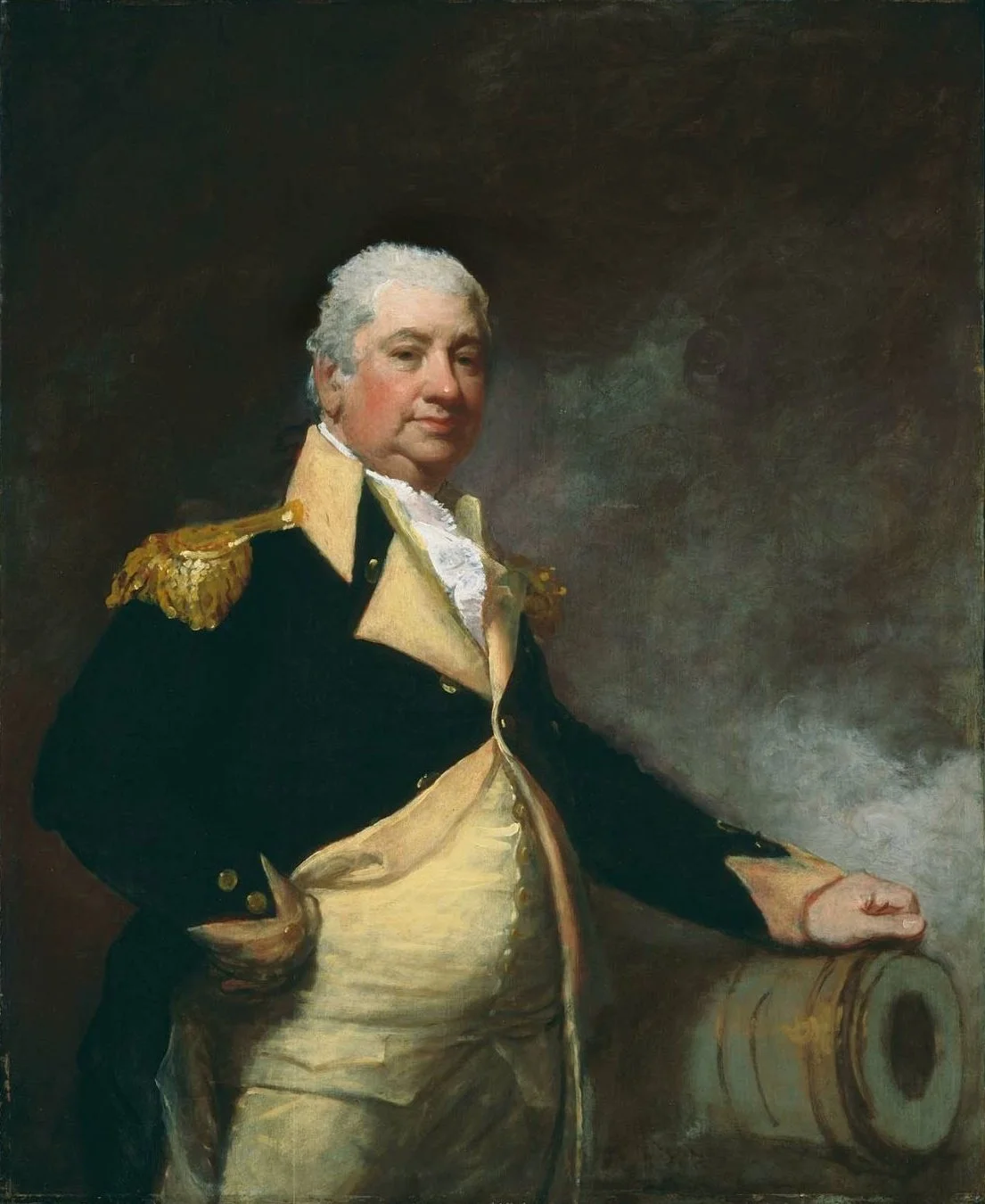

The images on the right side of the broadside provide a stark contrast from the various miseries depicted on the left. This side bares the legend “Irish Argument on American Soil.” The predominant image is that of Columbia, the personification of America, standing radiantly crowned with laurels in the foreground, a collection of American Revolutionary War-era soldiers standing armed behind her. Emanating from the rays of the sun on the hills behind her are the names “Barry,” “Montgomery,” “Sullivan," "Morgan,” and “Knox.” Each of these individuals represents an Irish-American hero of the American Revolutionary War. “Barry” is most likely Commodore John Barry, sometimes known as “the father of the American Navy,” who was born in County Wexford, Ireland. “Montgomery” is Major-General Richard Montgomery, whose death at the 1775 Battle of Quebec made him famous on both sides of the Atlantic as one of the most prominent “Irishmen who shed their blood in support of American Independence.” “Sullivan” refers to General John Sullivan, the son of Irish immigrants who settled in New Hampshire. The victor of many battles of the American Revolution, he was noted for crossing the Delaware with George Washington. The name “Morgan” presents the modern viewer with something of a conundrum; while there are several men with the surname Morgan who are considered heroes of the Revolutionary War, all of them are of Welsh extraction. It is possible that “Morgan” refers to one of these men who was mistakenly understood to be Irish in the late 19th century; it is equally possible that “Morgan” refers to someone else entirely, whose name would have been familiar to the 19th century view of this broadside. Given that the other names in this sequence are all military leaders, several of whom fought alongside George Washington, the former explanation is the likeliest, with the most prominent candidate being General Daniel Morgan. (And if anyone here knows who Morgan really is and it’s not this guy? Please, please . . . don’t tell me. No, I’m kidding, please let me know so I can update this!) Finally, “Knox” is Henry Knox, the son of Scots-Irish parents who rose through the ranks of the Continental Army to become a Major-General, eventually being appointed Secretary of War upon his retirement.

Columbia is wearing a Phrygian cap, or liberty cap – a symbol of the American and eventually the French revolutions. In her outstretched hands, Columbia holds a golden-hilted sword. Stepping forward to take the sword is Hibernia, the personification of Ireland, whose maiden harp - a symbol of United Irish Independence - lies behind her as manacles fall from her wrists. Below Columbia and Hibernia is written “Columbia to Erin. ‘Try this! In it I found my deliverance’” - a clear recommendation of revolution as a means of throwing off English colonialism. The legend below the right side of the broadside reads “Irish Argument on American Soil.” Above Hibernia stands a collection of men wearing tunics emblazoned with shamrocks, holding aloft swords and a banner that reads “Ireland A Nation.”

The two sides of the image are bisected by a series of banners and flags; the topmost one reads “God Save Ireland.” Below this, wreathed in shamrocks, are the American flag and the green harp flag, used as a symbol of an independent Ireland since at least the Catholic Confederacy of 1642. Between the flags, which are tied together, is a shield with the stars and stripes; below this hangs a green banner bearing the names “Allen,” “Larkin,” and “O’Brien,” encircled with a crown of laurels. The entire collection of images is framed in shamrocks strung along ribbons: Irish tricolor on the left, stars and stripes on the right. The upper left corner of the frame reads “Emmet” while the upper right reads “Meagher.”

“Allen,” “Larkin,” and “O’Brien” are William Allen, Michael Larkin, and Michael O’Brien, collectively known as the “Manchester Martyrs.” All three were Fenians and members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The three men took part in an attack on a police van in Manchester – England, not New Hampshire – on September 18, 1867 in an attempt to rescue two prominent Fenians, Thomas J. Kelly and Timothy Deasy. Although successful, in the process of this exploit, an English police sergeant was killed. Allen, Larkin, and O’Brien were convicted of murder on November 1, 1867, and in a speech from the dock, Allen declared “I will die proudly and triumphantly in defence of republican principles and the liberty of an oppressed and enslaved people.” The three men were sentenced to death and hanged at a public execution on November 23, 1867, after which the anniversary of their deaths was annually commemorated by those in the Irish nationalist movement. That’s Larkin on the left, Allen in the middle, and O’Brien on the right. This chromolithograph is interesting because it was produced in 1893 in the United States by an unknown artist, and it shares a lot of imagery with “God Save Ireland,” which was produced only two years later. There are, of course, the shamrocks, which predominate the image, even the martyrs themselves are arranged in a shamrock configuration with the Brian Boru harp (rather than the maiden harp) in the center, and then up to the top left, you have an Irish wolfhound (a symbol of Irish independence) against the backdrop of the the Irish landscape, while to the right, you have a cemetery with a Celtic cross, which is a nod to Catholicism. Larkin and O’Brien have little gold shamrocks on their neckties. And then down at the bottom, underneath the date of their execution, you even have the legend “God Save Ireland.” The fact that this image was produced over a quarter of a century after the death of the men it commemorates, a continent away from both their country of origin and the country in which they were executed, says something to me about their importance in the nationalist movement, but we’ll get to more about that later.

“Emmet”, of course, is Robert Emmet, the well-known Irish revolutionary who first joined the United Irishmen’s Rebellion of 1798. Emmet later went on to be one of the main architects of the Irish Rebellion of 1803, which is sometimes known as “Emmet’s Rebellion.” In spite of his rebellion’s failure, Emmet had a reputation on both sides of the Atlantic as a romantic Irish martyr for the Nationalist cause, whose post-execution legacy was immortalized by countless Irish poets, historians, and nationalists. By 1895, he was already the subject of poems, plays, and songs, and his legacy was evoked repeatedly during every subsequent movement toward Irish independence by everyone from Patrick Pearse to Eamon de Valera. (transition click) “Meagher” refers to Thomas Francis Meagher, a revolutionary Young Irelander who was convicted of treason and transported to Van Diemen's Land after his participation in the failed Rebellion of 1848. He was also considered a somewhat romantic figure as he had escaped the penal colony at pistol-point and made his way to North America in time to join the Union Army at the outbreak of the American Civil War.

This collection of Irish nationalist heroes and Irish-American Revolutionary War heroes, in concert with Columbia’s decidedly martial recommendation to Hibernia, makes the message of this broadside abundantly clear: the atrocities of the British in Ireland will not end without an armed rebellion. Like American independence, Irish independence will only be achieved through revolution.

However, there is one rather major caveat to the broadside’s thesis. If the colonization of Ireland by the British was seen as a template for the British to colonize America, then America wants to see itself as a template of throwing off British colonialism. But, it’s worth noting that the “colonized” throwing off British colonialism in America were themselves colonists. Although indigenous peoples were certainly involved in the American revolution, they didn’t benefit from the revolution, in that the promises of the American revolutionaries to their indigenous allies were immediately and repeatedly broken. So by 1895, there’s a real disconnect between the American understanding of the nature and causes and beneficiaries of the American revolution, and the actual conditions. And the former, the whitewashed interpretation of the American revolution prevalent in the late 19th century, is what informs those comparisons with Ireland’s status as a British colony. When in actuality, the condition of the Irish under British colonial rule more closely resembles the condition of the indigenous peoples in the newly formed United States of America than it resembles the condition of white colonists under British colonial rule in America. However, unpacking all of those nuances would require a completely different broadside.